MARGARET EVANGELINE

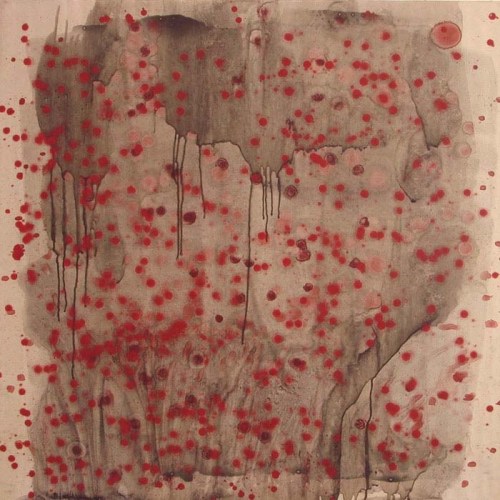

Uterine Fury of Marie Antoinette #90, 2000

oil on aluminum

48h x 48w in

By D. Eric Brookhardt

When artists die, they leave behind a "body of work." With any luck, their body of work holds up a little better than their own body at that point. Of course, dead artists are not always famous, but if they were any good, the work has a certain, almost palpable sense of life. The influential Germain philosopher Walter Benjamin went so far as to say than an art work has an "aura," while Marcel Duchamp once said that a successful painting has "a life" that lingers on for decades after it was made.

It sounds almost mystical, but the connection between bodies and art works, especially paintings, is very old, and shows no sign of abating any time soon. Margaret Evangeline's paintings at Simonne Stern seem to play off of this corporeal connection. Although there is no human figure suggested by their abstract swatches and splotches of paint on polished aluminum panels, neither is there any shortage of innuendo about the almost biological sense of life shimmering from their oddly atmospheric surfaces. Feminine innuendo.

The titles set a certain tone. In the Uterine Fury of Marie Antoinette series, 4-foot square panels of burnished aluminum glisten like sleekly outfitted race cars under thin layers of drippy oil paint and clear lacquer. Moire patterns of polished metal glow like waves on a metallic sea as richly hued slplotches of paint suggest drippy polka dots hovering over the surface. The silky metallic finish is a sleek touch, but Evangeline's deep reds, purples, and sooty dark oil pigments hark to the final days of the French dynasty, the revolution, and the guillotine.

So it's really quite theatrical. The metallic moire surfaces dripping with decorous splatters of bloody red and royal purple evoke big-time PMS at Versailles palace and the clamor of mobs who want something a little more carnivorous than cake. Yet, despite the cataclysmic overtones, their aura is as decorously intimate as a message left in lipstick on a bathroom mirror, a message perhaps sealed with the residue of a crimson kiss. The innuendo goes on for miles, and related works with titles like Taints and Poisons or Yellow Girl Blues do nothing to dispel the impression of highly motivated hormones in action. Elegant, fun stuff. Evangeline may live in New York, but her local roots are showing.