Photo courtesy of the artist.

Butterflies have been talismen of transformation and transcendence since prehistoric times. In “The Spirit of Butterflies: Myth, Magic, and Art” (Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2000), Maraleen Manos-Jones writes of one of their oldest depictions — in a wall painting of a religious shrine, dating from 6500 B.C., excavated at Çatal Hüyuk on the Anatolian plateau (present-day Turkey). For the later ancient Greeks and Romans, the butterfly was associated with the soul. The Greeks believed that the soul flew out of the mouth at death, much as a butterfly emerges from a chrysalis — something they depicted on sarcophagi. The ancient Greek word for butterfly and soul is our word “psyche” — a connection the 18th century sculptor Antonio Canova made in his sweet depiction of the goddess Psyche and her love-god hubby Eros (Cupid) holding a butterfly — holding Psyche’s soul — in their hands.

In modern times, some of the most memorable works of art have had butterfly motifs — from Giacomo Puccini’s tragic opera “Madama Butterfly” (1904) to Steve McQueen’s 1973 prison drama “Papillon” (the French word for “butterfly”).

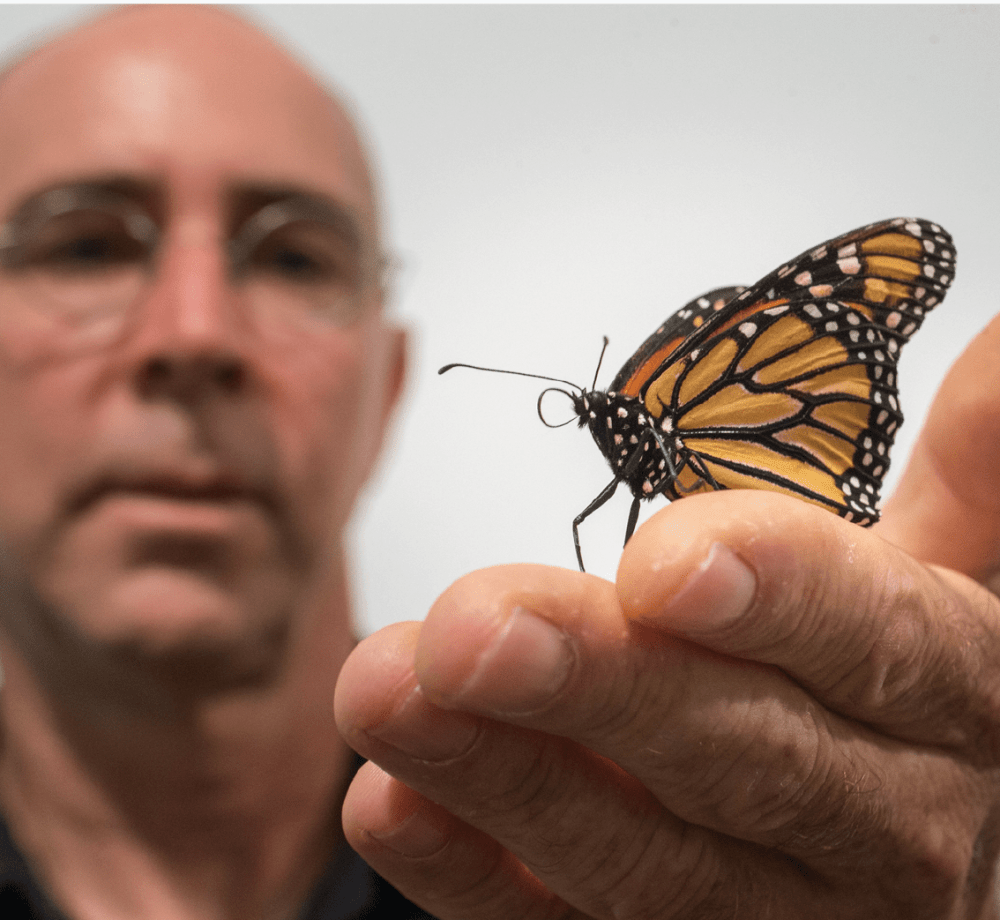

To the papillon oeuvre we can add the works of Paul Villinski, whose butterfly sculptures are the subject of the recent book “Villinski” (Vivant Books/Paul Villinski, 269 pages, $95.)

“Butterflies are impossibly beautiful,” Villinski is quoted as saying in David Revere McFadden’s essay for the book. “These ridiculously delicate creatures…fly many thousands of miles each year.”

Many of Villinski’s fragile frequent flyers are truly transformed, created out of recycled beer cans at his Long Island City studio in a building near MoMA PS1 where the Talking Heads recorded their “Fear of Music” album. Villinski’s creatures spiral and swarm over wire figures and wooden horses. They flit along guns, topping their barrels. They escape from overalls and are dramatically backlit on walls. Mostly, they tell the story of their creator, a man who is also fragile but enduring.

“They provide a touch of the magical in a world obsessed by science,” Bartholomew F. Bland, executive director of Lehman College Art Gallery, writes in his essay, “Kaleidoscope of Butterflies: Imagery and Iconography in the Art of Paul Villinski.” “Tellingly, the artist refers to their physical creation from the base metal of beer cans as ‘alchemy,’ the medieval idea of the transformation of matter….The idea of the beer can as a vehicle for intoxication has a powerful meaning for the person recovering from addiction, and it is also a strangely personal symbol.”

The seeds for Villinski’s addiction to drugs and alcohol were sown in a violent, peripatetic childhood. He was born 60 years ago in Maine to a mother, the former Jacqueline Whalen, who painted, and a father, Paul B. Villinski, who was a United States Air Force navigator and an abusive, mentally ill addict. All his life, his namesake has been in love with art and flight.

A self-described Air Force brat, Villinski moved regularly with his family. The one constant was his father threatening to take off his belt. When he did, Villinski would feel it. In one horrific incident, his 3-year-old body was covered in bruises.

When his father retired, Villinski received a full scholarship to Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire, one of the nation’s oldest and most prestigious prep schools. This should’ve been Villinski’s chrysalis, his cocoon for metamorphosis. Instead, he dropped out, beginning an odyssey of travel, reading, drugs and alcohol that would bring him to study at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and graduate from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Making the decision to get sober in 1992, the environmentally minded Villinski also decided along the way to trade his LeFranc and Bourgeois oil paints for New York City detritus — old gloves and LPs, broken police barriers, discarded shipping pallets and empty liquor bottles that echoed his family’s history of addiction — to create things with wings.

“Lately,” he writes in the “Artist’s Statement” at the end of the book, “the things I need to make in the studio seem to choose me rather than the other way around, probably because I’ve stopped trying to keep the influence of my own biography in check. After three decades of practice, I’m finally willing to let whatever it is I actually know and care about find form in my work.”