LONG ISLAND CITY, N.Y. -- Paul Villinski is not sure why he is obsessed with salvaging discarded objects and transforming them, but that's long been his MO as an artist: He takes discarded beer cans and turns them into wall displays of colorful butterflies; he takes work gloves left in the gutter and stitches them into giant wings, the gloves' fingers fluttering like feathers; and when he was in flood-ravaged New Orleans in 2006, he roamed the streets looking through the trash people carted out of ruined homes and collected their warped old records, then began working with those too.

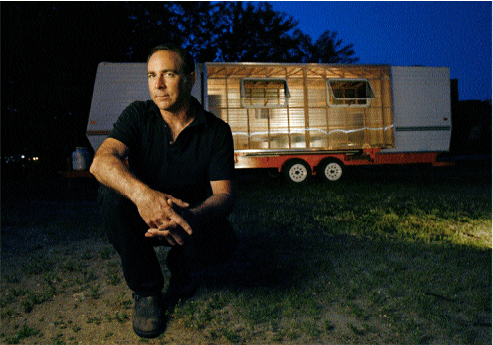

But New Orleans also inspired a more ambitious salvage job -- the transformation of a discarded government trailer, the sort that the Federal Emergency Management Agency had bought by the tens of thousands for use as temporary shelters after Hurricane Katrina, then scrapped because they contained toxic fumes. Villinski has gutted a 30-foot Gulfstream trailer here in the Socrates Sculpture Park, just across the East River from Manhattan, and is turning it into a self-sustaining “Emergency Response Studio” that would enable an artist to set up shop in a disaster zone such as New Orleans while spotlighting the "absurd on many levels" waste in the government's emergency housing program in the Gulf region.

Indeed, the project is destined for that area, as part of “Prospect.1 New Orleans,” a biennial exhibition opening Nov. 1 of works by dozens of artists, many inspired by the hurricane and its aftermath: Los Angeles' Mark Bradford is building a wooden ark, using the shell of a deserted home; Jamaica-born Nari Ward is creating a new version of a bulldozed church that was in a converted boxing ring, embracing the two symbols of self-empowerment; and Wangechi Mutu, originally from Kenya, is creating a "ghost house" where a local woman was cheated by a contractor, who built a foundation, then absconded with her money.

"We'll have paintings too, pretty paintings, sad paintings and a lot of photography," said Dan Cameron, a former curator at Manhattan's New Museum who is organizing the show with support from the Andy Warhol Foundation, among others.

The 48-year-old Villinski began his career as a painter, then segued into three-dimensional work. The son of an Air Force navigator who had the family constantly on the move, he figures his interest in discarded objects may have stemmed from "a kind of feeling of low self-esteem. I actually felt I didn't deserve things that were terrific out of the box. . . ." Villinski doesn't get too deep with this sort of speculation, however, noting that before the beer cans and old gloves, "I rescued British sports cars for a while."

His loft home and studio is in a four-story brick building that once housed three members of the Talking Heads rock band. On a recent day, his assistant was putting coats of luminous blue paint on some of the “beer can butterflies” that will adorn a wall at a company's offices in Oakland. Villinski turned the records he found in New Orleans into butterflies too, then started doing the same with his own LP collection, taking the vinyl that once played Fleetwood Mac and Jimmy Cliff and warping it into the delicate symbols of transformation. Some of the butterflies are attached by wires to old turntables, so they revolve, part of an installation ("the soundtrack of his life") destined for the Museum of Art and Design’s new building opening in September on Columbus Circle in Manhattan.

Waste not, want not

The studio also had pieces of balsa wood laid out on a table, what had been the model for his trailer project until a parks employee cutting the grass at the sculpture park ran into it with his lawn mower while Villinski was out of town. "I got back last night and have been sorting through what's left," he said before setting out for the riverside site that was an illegal dump until sculptor Mark di Suvero led a campaign to put it to better use.

Villinski's "Emergency Response Studio" is one of 16 projects displayed there, or being created, as part of an environmentally themed "Waste Not, Want Not" show. His trailer is not actually one of the 143,123 FEMA bought from several manufacturers for $2.7 billion after Katrina, though Villinski did try to get one of those through a General Accounting Office website that was auctioning them off. But the government stopped the sale, and started buying the sold trailers back, because of the problem that turned the program into a fiasco -- formaldehyde fumes from glues used to secure rugs, plywood and other components.

Just this month, New Orleans officials said that on July 1 they will begin enforcing an ordinance prohibiting residents from continuing to live in the temporary shelters, nearly 5,000 of which remain in use in the city.

Villinski thus had to settle for a similar trailer, from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which was disposing this one through the GAO site after using it in Delaware, where it had been abandoned and taken over by a weasel and small rodents. "It cost $5,015, which was a premium price considering the condition," he said.

He has gutted the inside and cut through the aluminum siding to create a "slide-out" with thermal panes. Another wall will become a drop-down deck while the now-cramping roof will give way to a 9 1/2-foot-wide geodesic dome. Farther above will be a towering mast supporting a wind turbine that, along with solar panels, will provide power for the trailer. The insulation? It's recycled denim, scraps left over from when they make blue jeans.

It will be a busy summer for Villinski and a volunteer, a man who was visiting the sculpture park and offered to help get the "off-the-grid" trailer ready for the 11-week show in New Orleans. While Villinski sees it as a commentary on the government's wastefulness, he also makes the case that just as the public needs medical workers and other emergency crews at disaster scenes, there should be a way to embed artists, who "could inspire hope or an-out-of-the-box way of getting out of this."

He also sees his trailer as a prototype, suggesting a way FEMA could salvage all those trailers destined for the scrap heap, "although it is a rather ridiculous amount of work to gut the thing and start rebuilding it."

Another thought came to Villinski as he stood outside the flimsy hull of the gutted trailer.

"I've gone through different disciplines, but there is some kind of fanatic connection between the things I'm doing. In a sense this FEMA trailer is just a really big beer can I'm transforming into something of beauty."

Written by Carolyn Cole